My conversation yesterday with the scholar (and proud dad) Mahmood Mamdani has sparked a ton of conversation and argument and resonance, so I wanted to bring you an edited transcript.

Mamdani is an Ugandan anthropologist and political scientist and one of the world’s most influential thinkers on colonialism and its long shadow over modern life. We spoke about the ideas of power and justice and belonging that have defined his career — and that have become of great public interest now that his son, Zohran Mamdani, is about to be the next mayor of New York City. A parent’s ideas are not necessarily revealing about a child’s, but in this case, the rhymes between the father and the son are unignorable.

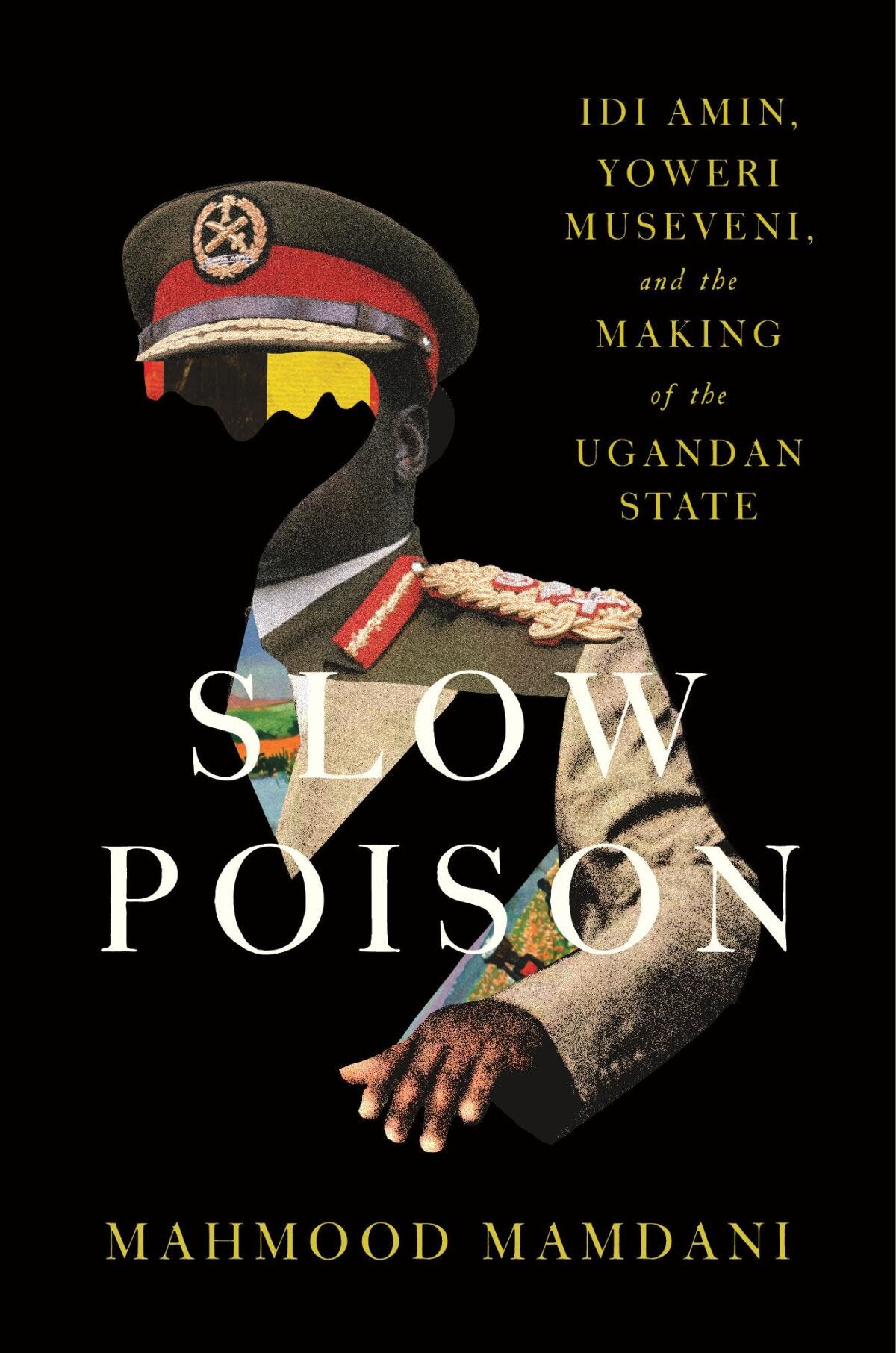

Professor Mamdani is the Herbert Lehman Professor of Government and a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, the chancellor of Kampala International University, and the author of many books, including Good Muslim, Bad Muslim, on the roots of the War on Terror in the Cold War; Neither Settler nor Native, about how modern nations decided who belongs; and Citizen and Subject, the classic study of postcolonial African politics. He has a new book out, Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State, a study of his home country’s post-independence strongmen, and a memoir of his own political and academic journey.

Below, for our supporting subscribers, we present a full transcript, lightly edited for clarity, of our conversation.

I’m a father, but my children are very young, and I sometimes think abstractly about the work that I’m doing and hope that in some way it will both shape the intellectual atmosphere of my children directly, what we tell them, the stories we tell them, the ideas we give them, it’ll shape the kind of people they are. And then, of course, I also hope that we’re shaping the world in which they will live.

And so I wanted to ask you first, as someone who has worked for so long on so many of the themes that are front and center now in, not just in this election but in American life, in New York City’s life around authoritarianism, around freedom, struggles around who belongs, who is included, who is excluded, there’s some elections that are fought on niche economic issues or whatever, but this was really an election that your son won that seemed quite connected to things you’ve spent your whole life thinking and writing about. And so I wonder, what is that like, as a father slightly ahead of me in the curve of fatherhood, to see your son elected to such a powerful position, in keeping in many ways with things you have been thinking about and working on for much of your life?

I have mixed responses to it. On the one hand, I am like anybody would be, a very proud father. I don’t want to claim that I saw this coming. I certainly didn’t see it coming. I was really surprised when he said he was contemplating running for the position of mayor of New York City, but then he’s not somebody who is given to convention, and he’s not somebody who is afraid of the odds no matter what they are against him. So that’s one feeling.

The other feeling I have is, well, this job is going to bring a mountain of responsibilities on his back. Like everybody, just about everybody has noted and commented, he’s a young man, he’s 34 years old. He has a lot of chutzpah. He’s open to experimenting. He understands fully well that he doesn’t have the kind of breadth of experience which can be equal to a job like this, and that therefore he will have to develop a team which will pull together and make up as a team what they may not have as individuals.

But it’s still intimidating for somebody like me, close enough and yet not in it. So having to watch it from a distance, it’s like a fast car race, and you are on the sidelines and your son is at the driving wheel, and you just keep praying and hoping that all will be okay.