How to think about China

Veteran foreign correspondent Jane Perlez explains the central great power rivalry of our time

There is kind of a lot going on right now. Even as this week the United States ventures into the unprecedented territory of seeing a former president stand criminal trial, the world scene is fraught — from Ukraine to Israel to Iran and beyond.

But what is arguably the biggest and most important foreign policy story of our time often gets lost in the international turmoil. The rise of China is less a story of flash points and acute crises than a story of a simultaneously slow and fast juggernaut reshaping the basic architecture of the world — and many of our own societies.

How should those of us who are not China hands, who don’t know much about China, who have been affected by its rise without entirely understanding its ends — how should we think about China today?

To help us out, we’re bringing in one of the smartest China watchers in the game. Jane Perlez, foreign correspondent and former Beijing bureau chief for The New York Times, first visited China as a university student and has been a gifted explainer of its inner workings and outer strivings ever since.

Here’s some of what we got to ask her: What is the Chinese leadership seeking in the world? Why is it interfering in the U.S. election? What do Chinese people want — is continued prosperity enough, or is there a clamor for democracy coming? Why are some Chinese members of Gen Z refusing the culture of overwork in favor of what they call “lying flat”? Should the rise of China and its success make us recalibrate our assumptions about what is possible under authoritarianism versus under democracy?

Perlez’s new podcast, Face Off: The U.S. vs. China, co-hosted with historian Rana Mitter and drawing on the expertise of a host of China scholars, delves further into the fraught China/U.S. relationship, covering everything from naval disputes over territory in the South China Sea to Apple’s dependency on Chinese manufacturing, to why the weakness of the Chinese domestic economy is demoralizing young people.

If you’re like us and you know how important it is to understand China but, to be honest, it has kind of gotten lost in the shuffle, this conversation is for you. Dive in!

A request for those who haven’t yet joined us: The interviews and essays that we share here take research and editing and much more. We work hard, and we are eager to bring on more writers, more voices. But we need your help to keep this going. Join us today to support the kind of independent media you want to exist.

And today we’re offering you a special discount of 20 percent if you become a paying subscriber. You will lock in this lower price forever if you join us now!

You first visited China as an adolescent and have continued to be one of its closest watchers in the West ever since. How do you understand where China is in the arc of its journey at this moment? And how does that position set it up for what you call this “face-off” against the United States?

I was an Australian university student when the Cultural Revolution was raging across China. The national student travel organization organized a summer trip to China.

I am sometimes reluctant to mention this, since often the reaction is, “Oh, Red diaper baby.” Not the case. We were 50 students of all political beliefs: slightly left of center, conservative, and apolitical (I was the lattermost). We had chosen China over Indonesia (too close), India (food at that time questionable), and anyway China was the most interesting.

The overwhelming takeaway from that trip was that, even in the Mao-induced chaos, you could see that China would become a huge, well organized, and interesting power. How long that would take was not at all clear. It was obvious that China was weak militarily, and that the convulsions were so deep that it would take a while for the country to reorganize and build cohesion.

By the time I came to live in the United States a few years later, you could already see that China was quickly getting its act together, and that the U.S. was responding, thanks to the Nixon/Kissinger diplomacy. Then came China’s acceptance to the World Trade Organization at the end of the Clinton era.

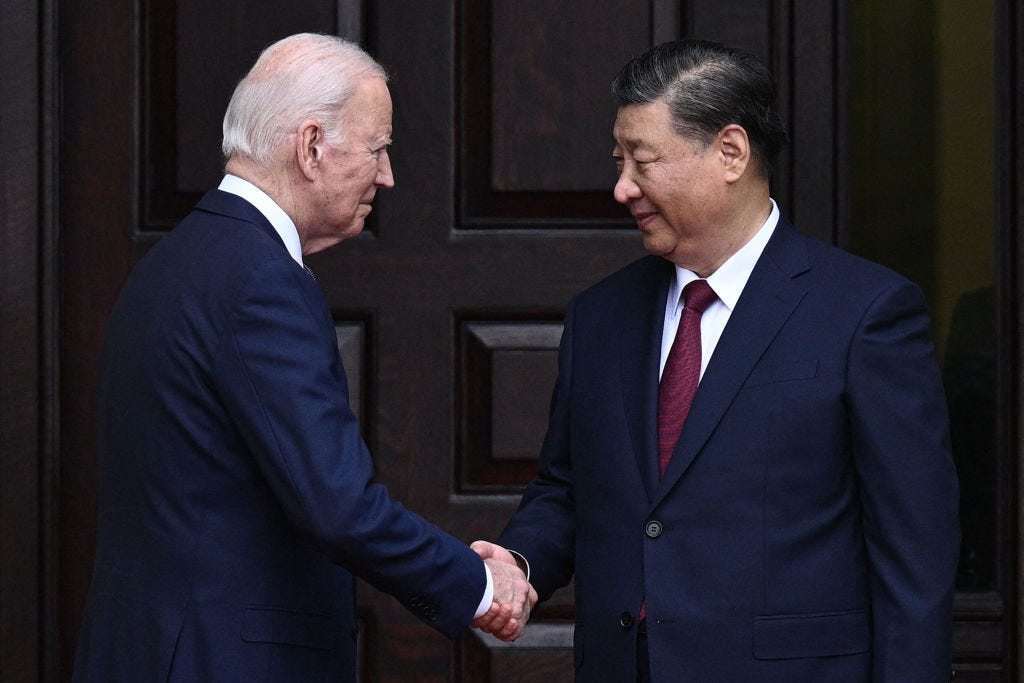

Now the two sides are in a deep, far-reaching struggle — what our podcast calls a “face-off” — in every realm.

One reflection I’ve had on my visits to China was that I was taught this was not supposed to work. I was raised on an American, perhaps Western, civic education that says authoritarian societies cannot be like this: cannot deliver this level of prosperity, cannot lull this many people into enjoying quotidian liberties and giving in to the lack of political freedoms, cannot create and innovate when people are living under the fear of thought police.

If you’re asking what the Chinese think about their system of government it’s almost impossible to know. But if you get to know a variety of Chinese people — and I stress variety — you can begin to understand that economic welfare is the premium concern. People can adjust to the surveillance, to the thought police. The economy is overwhelmingly important.

But at the moment that economy is in bad shape. There is now an unprecedented “lying flat” movement that we talk about in our episode on the economy; these are people under 25 years old who have decided that the hyper-work model that has helped China succeed is not the way they want to go. Gen Z people are opting out, leaving their urban places, and in some cases going back to the countryside. Some are just chilling out, others are taking a break.

I’m very skeptical that it will amount to anything like even a nascent democracy movement. I’ve asked Chinese people whether this could develop into serious protest. They tell me that the regime watches “lying flat” like a hawk. There’s too much surveillance for it to develop into opposition.

How much of a shock do you think the example of China’s rise has been to the Western understanding of the possible? I wonder if you think China’s success — and what it says about the importance of democracy or the lack of democracy — is related to the crisis of belief in democracy in many parts of the West?