Heather McGhee on reparations as "seed capital," Trump and Biden as "meaning makers," and more

The writer and policy wonk on why paying America's debts would benefit everyone, how Trump helps people figure out what they think, and how Democrats can learn to reach voters more deeply and durably

Here is a simple, solemn promise to you: by the time you read Heather McGhee’s vision for racial reparations below, you will never think of the issue the same way.

McGhee is an author, activist, and policy wonk. We last spoke to her in 2021, right after the publication of her book The Sum of Us, which argued brilliantly that fighting racism benefits all Americans, because racism has cost all Americans so much.

Why? Racist policy in the U.S. has been a national-scale study in cutting off your nose to spite your face. In what McGhee has famously called “drained-pool politics” (she writes about how, in the late 1950s, communities refused to desegregate their New Deal-era public pools and instead simply drained them, depriving everyone of access), the country’s leaders have chosen to deprive all Americans of public goods rather than extend them to Black people. The zero-sum arguments of today’s authoritarians and yesterday’s neoconservatives are simply the latest variations on the theme.

More recently, thanks to a new reparations commission in New York State, McGhee has been thinking about that aspect of public policy through her Sum of Us lens. She argues here, too, that taking responsibility for old debts and finally providing benefits due Black Americans takes nothing away from white Americans. Economic justice, says McGhee, isn’t the zero-sum game that many in the center or on the right would have people believe. Indeed, she tells us, righting America’s racial wrongs, via reparations, for instance, would pay what she calls a “solidarity dividend” — providing seed capital for the multiracial democracy the country could be.

We talked to McGhee about the actual prospects for reparations for Black Americans, what a truly multiracial democracy might look like in practice, and how in order to make that possible the Democratic Party needs to put forth new kinds of leaders — ones who can tell the stories that help people create meaning in their lives — in order to compete with populist alternatives on the right.

And a request for those who haven’t yet joined us: The interviews and essays hat we share here take research and editing and much more. We work hard, and we are eager to bring on more writers, more voices. But we need your help to keep this going. Join us today to support the kind of independent media you want to exist.

And today we’re offering you a special discount of 20 percent if you become a paying subscriber. You will lock in this lower price forever if you join us now!

Your book makes such a compelling case that addressing racism is not a zero-sum game. Fighting racism benefits white people also. New York, as you know, just launched a Reparations Commission, and I was just thinking that, probably, of all the remedies out there, it's the one most perceived as zero-sum. So I wonder how you see and situate the growing movement toward reparations in the context of the tension between zero-sum and non-zero-sum thinking on race.

Reparations are not zero-sum. I think of reparations as seed capital for the nation that we are becoming. We’ve gone so far in this country on the backs of the descendants of a stolen people who’ve contributed unbelievable amounts to this country's prosperity and ingenuity and culture and intellectual life, and we've done so as Black people have faced every possible constraint and barrier.

It is so important for economic reasons for this community, which is an underinvested asset in this country, to have the kind of wealth cushion that turns people's dreams and aspirations into reality. It’s so important for our democracy for everyone to know that they live in a society where when government harms you, they make it right. There’s no sense that, “Oh, time has passed, and so the seven members of the city council that voted to take your family's land are no longer with us, and therefore you will continue to suffer the consequences of that for all time, and there will be no apology and there will be no repair.”

That’s not the kind of society we want to live in. It’s not the kind of society that we created for Japanese Americans, that was created for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. That is not the kind of society that upholds human rights and equal protection under the law. I also think that our country is a can-do country, and there has been this tremendous shift in public will and recognition that the mythology we've been sold about American innocence was a lie. I spend most of my time, multiple days a week, on the road traveling across the country talking to audiences about these issues. They’re in central Pennsylvania and central Missouri and many, many red and purple communities, and there is a recognition that we need to do better.

But this country is a country of people who want an app for fixing something. We’ve created, as a racial justice movement, more awareness and agreement that harms have been done. Americans want to say, “OK, so what do we do now? How do we fix it? How do we keep moving towards the future?” So I didn't originally write a ton about reparations in the book. In my career as an economic policy advocate, I focused a lot on the racial wealth gap, but the Overton window was not yet open on reparations. But it’s clear to me now from the past three years that I’ve spent on the road that there is a grassroots movement for reparations and, even beyond that, a curiosity about the possibility of reparations, largely in white communities, that is about wanting to overcome and wanting to be the country that lives up to the myth that we were sold.

I love how you relate it to this idea of the seed capital for dreams coming true. But with this issue of reparations, and also on issues like climate, the opposition is so good at defining them in terms of what will be taken away from you. Often, those of us who want these things are not equally and oppositely good at narrating the gains — so that, on climate for example, people don’t see a picture of themselves as being able to breathe freely and drink water without anxiety, but they can vividly imagine not being able to eat beef or drive a car.

Similarly, on reparations, “what is being taken” has been so weaponized and ginned up. But you're talking about seed capital for dreams. If this were to happen in a big way, to go well beyond a commission exploring it, start to paint a picture of an America with reparations, with that cushion of Black wealth. What does it start to look like? What starts to happen around you? What's the crackle and pop of that America?

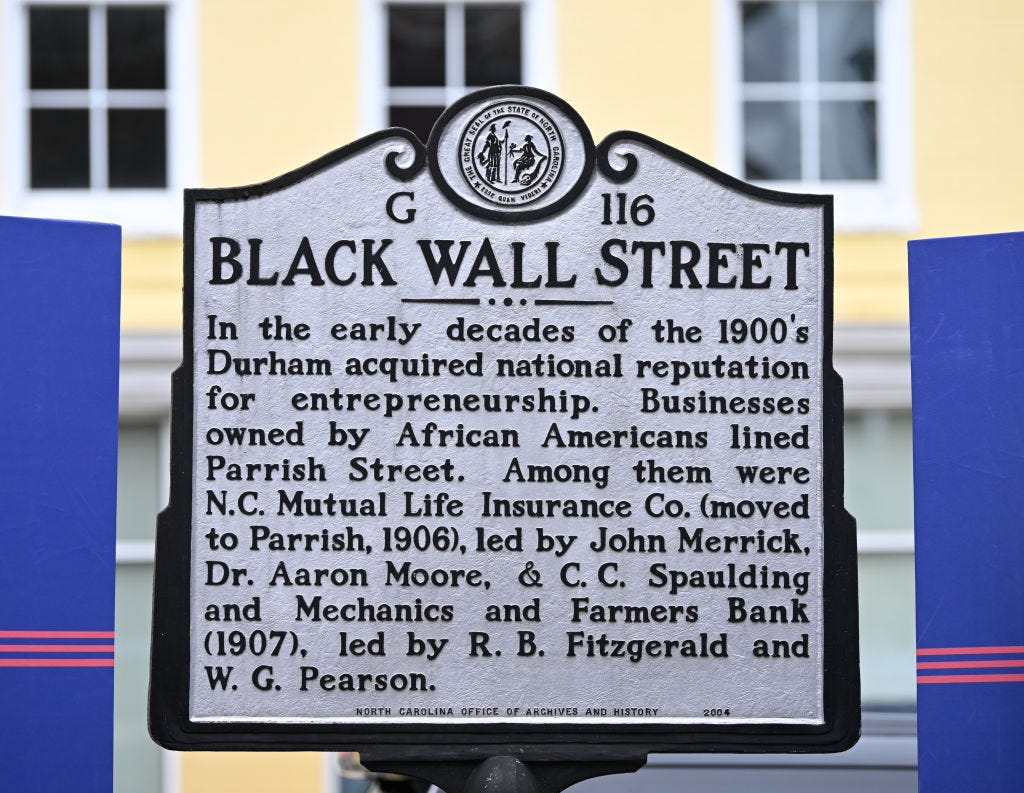

It’s an America where there are Black Wall Streets and Rosewoods. It’s an America where Martin Luther King, Jr., Boulevard is not the most disinvested, boarded-up block in your community, but rather is a place where there are thriving Black businesses and schools and places of worship.