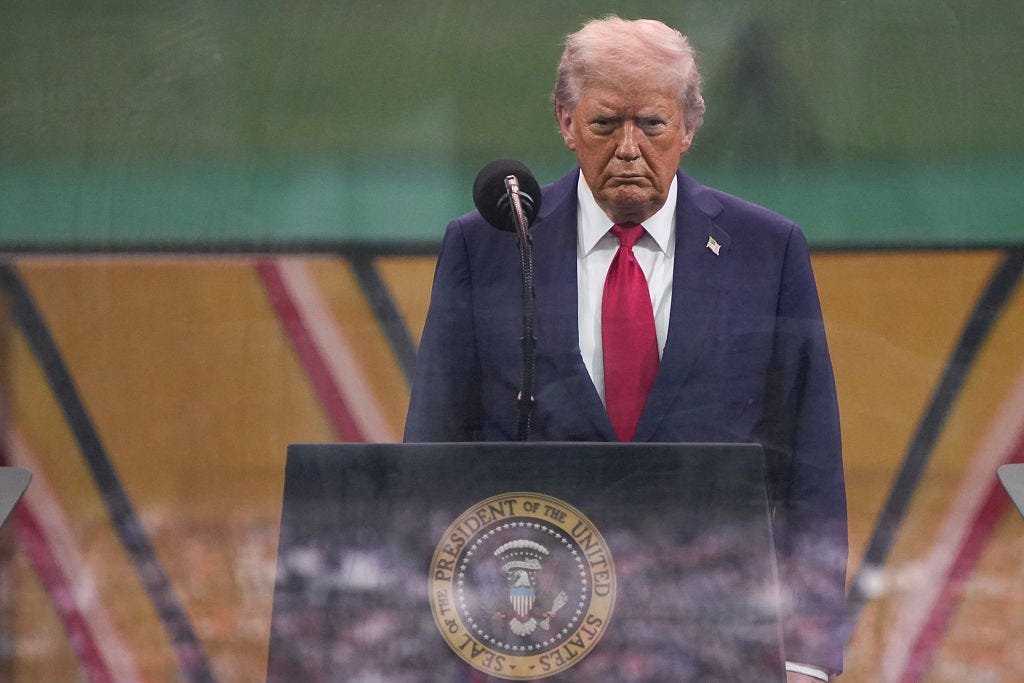

ESSAY: A bad parade is a good sign

A society can either invent things like jazz and kimchi tacos or stage awe-inspiring lockstep parades. It cannot do both

Join us today, Monday, June 16, at 12:30 p.m. Eastern, when we talk again with scholar of authoritarianism Ruth Ben-Ghiat. You can watch our Live events on your desktop at The Ink or on your phone or tablet with the Substack app.

The country that invented jazz was never going to be good at putting on a military parade. It was never going to be us.

In the …