Your pain, their gain

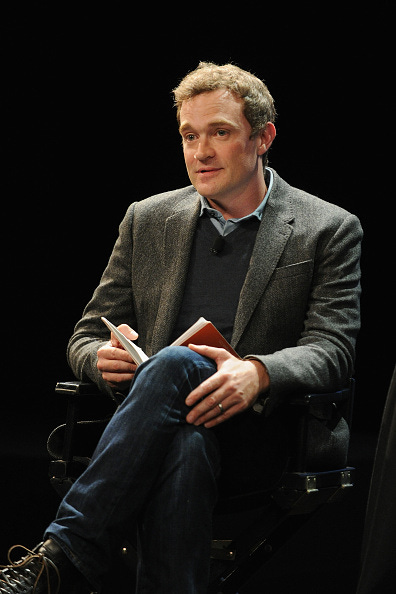

A conversation with Patrick Radden Keefe about his magisterial and breathtaking new book on the Sackler family and the opioid crisis

Welcome to The.Ink, my newsletter about money and power, politics and culture. If you’re joining us for the first time, hello! Click the orange button below to get this in your inbox, free. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support this work.

When I began to write and speak critically about big philanthropists, I would often encounter the “at…