To prevent tyranny, fight inequality

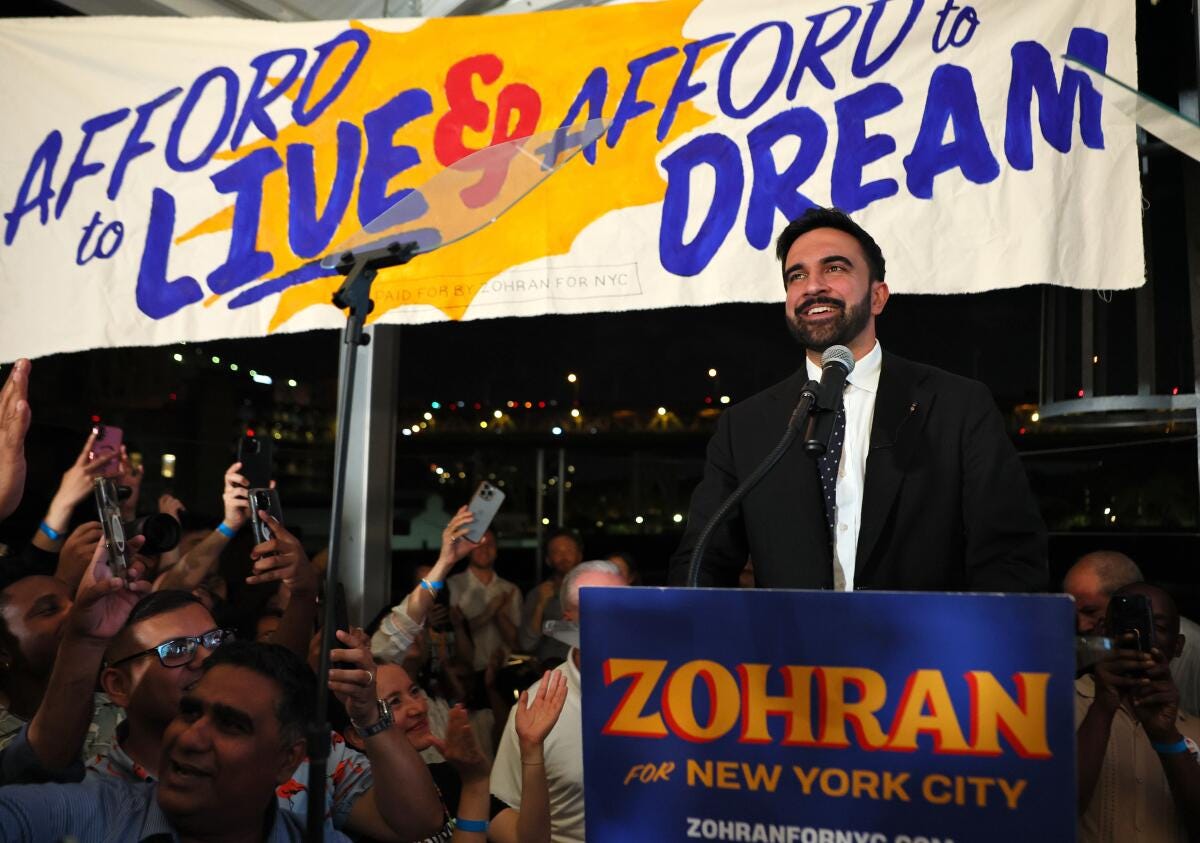

Waleed Shahid on how inequality fuels authoritarianism, and the lineage that connects FDR, the United Auto Workers, and now Zohran Mamdani

Reminder: Today, at 1:30 p.m. Eastern, we have a special Book Club talk with Suleika Jaouad. Watch on desktop at The Ink or join us from a phone or tablet with the Substack app.