Roger Cohen's “stubborn hope” for democracy

Talking to the veteran New York Times foreign correspondent about the emotional roots of this age of nationalism, what he’s learned about hatred and atonement, why he became an American, and more.

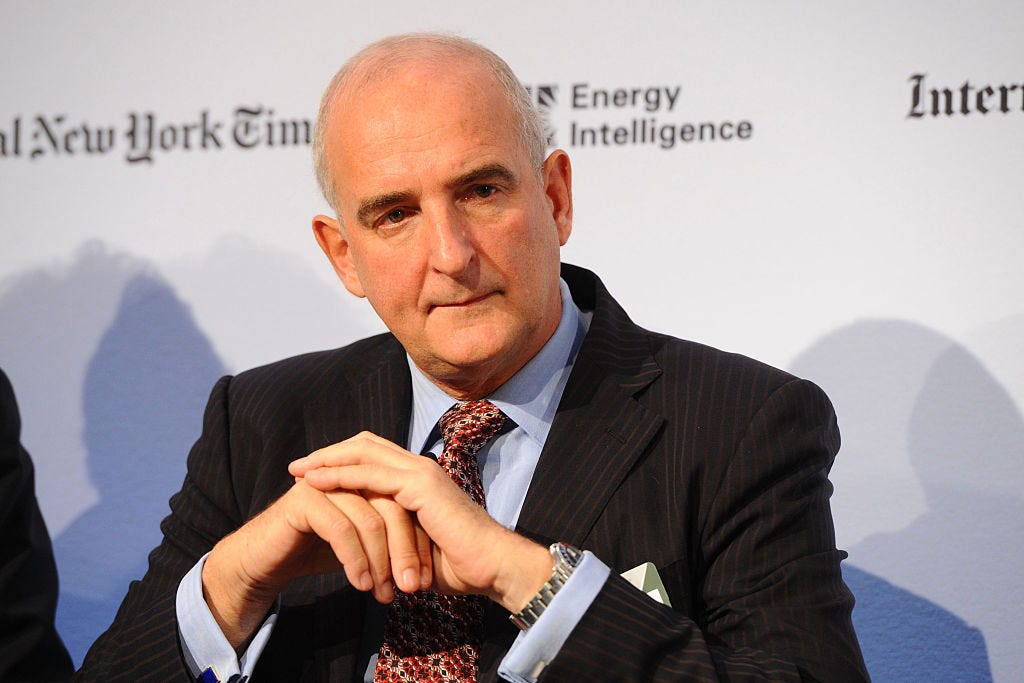

I will embarrass Roger Cohen, the veteran New York Times foreign correspondent, by telling you that he, as much as anyone, taught me how to write about the world. Not in a classroom or even through an actual relationship at first; just through reading him as a young man who wanted to write, wanted to cover the world, wanted to meditate on the dilemmas of the age.

I wrote to him when I wasn’t yet a reporter, just words of admiration. Then I was lucky enough to get a job at The New York Times, in India, and I wrote to him some more, asking for advice, appreciating his pieces, trying to learn from him. And he always wrote back, always spent those minutes he didn’t have to helping a young writer find his way and find his voice.

I tell you this not only because it mattered a lot to me but also because I think it gets at something fundamental in the spirit of Roger’s dispatches from around the world, which are collected in a new book collection out this week, An Affirming Flame. In an age of so many dehumanizing forces — from the crushing pressure of the forces of big capital to the ascendant authoritarian movements to the soul-sapping technologies that consume our days — Roger has chased the flame of the struggle for humanity.

His body of columns from around the world, collected in An Affirming Flame, cover various topics, bouncing from here to there. But there are deep threads connecting the work. It amounts, I think, to an inquiry into whether the better angels of human community can prevail in the end: whether atonement and forgiveness can prevail over hatred and resentment; whether democracy can prevail over authoritarianism; whether love can prevail over hate; whether the rule of law can prevail over force.

I am so happy to be sharing this conversation I had with Roger with you all, below. You don’t want to miss this one, trust me.

And if you’re a paying subscriber, you also have the option of listening to this interview in the podcast format. If you haven’t joined yet, today may be the day.

In your new book, An Affirming Flame, you call this “the Age of Undoing.” What do you mean?

A lot of assumptions that we had about the world heading in a liberal democratic direction have simply collapsed. There's been an undoing of the international order. There's a transition underway from an American-dominated world to one with really no single power dominating. So it’s a very combustible and, I think, uncertain situation. The international legal order has been violated, not for the first time obviously, but severely violated by President Putin's decision in flagrant violation of Article 2 of the United Nations treaty to invade a sovereign state, try to destroy that state, and occupy a large part of it.

A lot of our certainties about the world were also undone by the COVID-19 epidemic, which stemmed from Chinese concealment initially of what was going on, and former President Trump's period of long obfuscation, all of which resulted in the contagion being much worse and having devastating consequences. People talk openly these days about the possibility, remote perhaps, of nuclear war. People did not do that even a short while ago. There's, I think, a feeling of uneasiness in people's lives, uncertainty as to what will happen even in the coming year. So, yes, a lot has been undone in terms of the framework within which much humanity lived their lives.

In your roaming around the world, one of the things that makes your columns work as a collection is that certain themes keep coming up again and again, and you pursue them. One of them, obviously, is hatred, and you start the introduction to this new book talking about hatred. You conclude something that I have to say sounded both very true and very terrifying to me. You quote the Polish poet Wisława Szymborska about the superior powers of hatred. "Hatred," she writes, "vaults the tallest obstacles. It creates erotic ecstasy." She writes, "Since when does brotherhood draw crowds? Has compassion ever finished first?" And about hatred, she writes that it knows how to make beauty.

It struck me as so profoundly true. I wonder in your long coverage of hatreds from the former Yugoslavia to elsewhere in Europe, looking at your own origins in South Africa, and beyond, at the United States, have you come to share her conclusion that hatred has it easier in a way that democracy is always outgunned and at a disadvantage?

Democracy and freedom are perpetually at risk. They're fragile, and great vigilance is needed to preserve them. That said, they're also powerful in the sense that there is a very strong human yearning to be free, and there's a very strong human yearning to be able to make choices about governance, about who is going to govern their country. But to underestimate hatred, to think that we've somehow overcome it or had reached with the new millennium and the end of the Cold War, some superior stage of development where hatred would disappear, and countries would realize the benefits of cooperation and hatred would be set aside, that was a very dangerous illusion.

The appeal of nationalism, of scapegoating, and of identifying an enemy is very powerful. It creates a tribal form of allegiance and it gets the blood up. I mean, look at how former President Trump began his campaign and vaulted immediately to the first place among potential Republican candidates in 2015, simply by saying that Mexicans were rapists. It got people's blood up. It focused on an enemy, and often these enemies are imagined.

A lot of human beings are looking for meaning in their lives, particularly in our atomized societies today, where people spend more and more time on social media. It’s supposed to connect us and does in some ways, but also, I think, it isolates people, as of course COVID-19 did, too. So they're looking for the savior figure who tells them who the enemy is and who to hate. And so, yes, hatred is a powerful and fundamental human emotion, and any suggestion that it's somehow been overcome once and for all is foolish and misguided because, as I said at the beginning, freedom and democracy are fragile. That is a lesson we all have to learn. A republic, if you can keep it, as Ben Franklin put it at the foundation of the United States. If you can keep it.