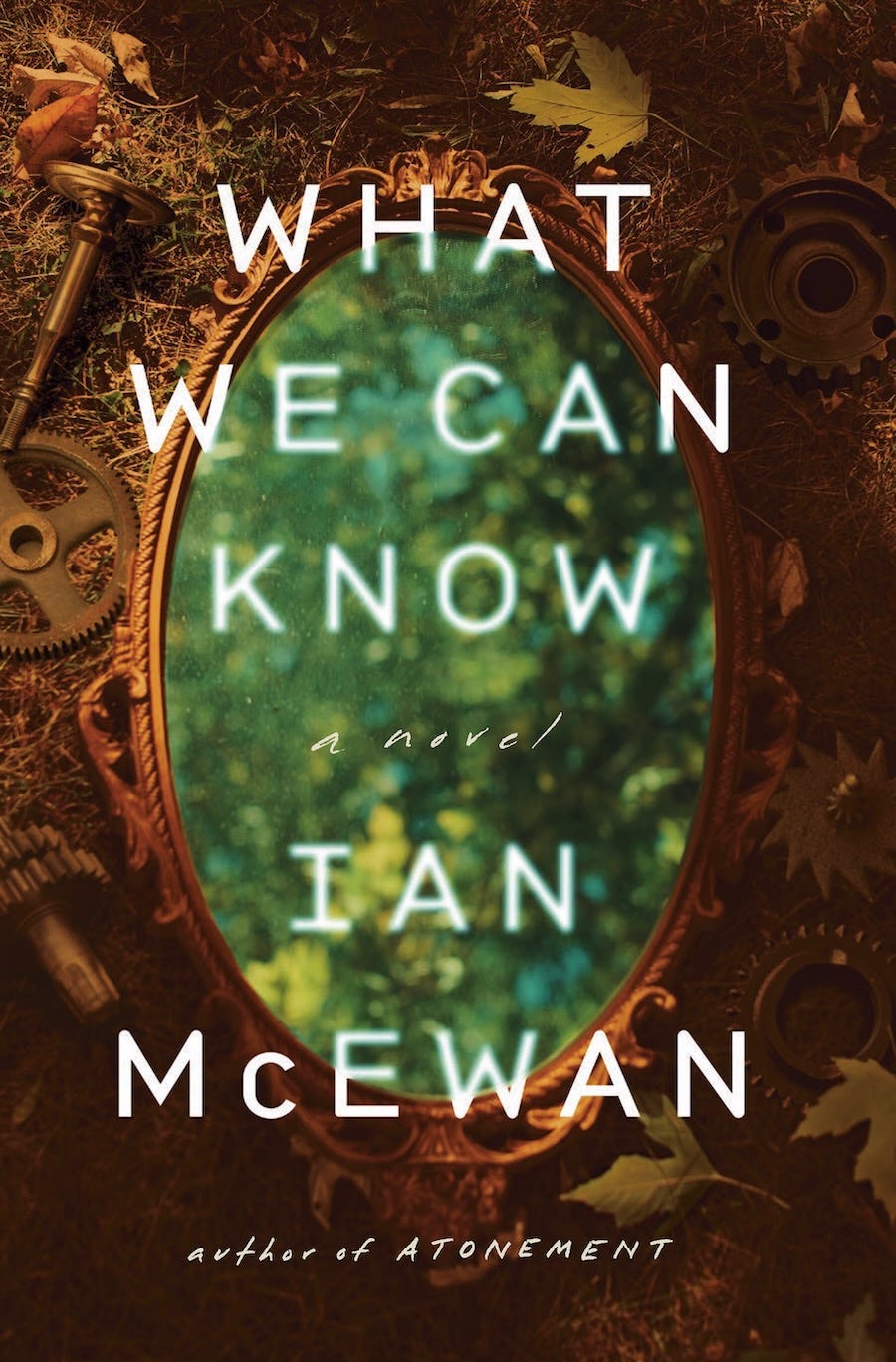

"Atonement" author Ian McEwan on the world after climate disaster

The prizewinning novelist on his latest book, "What We Can Know," and how a dystopian novel can be an antidote to metaphysical gloom

In Ian McEwan’s latest novel, What We Can Know, everything we fear today will go wrong already has.

A perfect storm of populist leaders, climate change, greed, and technology unleashed — the “Inundation” —has forever changed the world. The U.S. is mostly submerged and governed by rival warlords. Some survivors look back at the pre-apocalypse 21st century with yearning for all we had that they likely never will: lush gardens and tall trees, good food, wildlife, fresh air, international travel, and relative peace. Others remember us with contempt. How could we have seen the signals and done nothing about them? In England, where the story unfolds, a literary scholar named Tom Metcalfe navigates his diminished present without complaint, choosing to immerse himself in researching a dinner party that took place in 2014, and a poem that was read aloud there, and then lost to history.

Is What We Can Know about living with a kind of cognitive dissonance that allows contentment within strife? Is it a plea for us to wake up before it’s too late? It’s both of these and more, most notably, how we will be judged by future generations, and the contradictions that lie within us all.

McEwan is the author of nineteen novels and two short story collections. His first published work, First Love, Last Rites, won the Somerset Maugham Award; his novel Amsterdam won the Booker Prize; and novels, among them Atonement and The Children Act, have been made into movies. We caught up with him via Zoom from Cleveland, a stop on his book publicity tour, to talk about the new novel—and about avoiding “metaphysical gloom.”

What We Can Know is set in the next century, after decades of war and ecological disasters. Your main character spends most of his time looking back at our present via digital archives with a combination of envy and nostalgia. What led you to frame the novel in that way?

I was looking for a way of talking about our present and how future generations will view us—looking back not only on disastrous decisions around, say, climate change, nuclear weapons, and so on—but also all what we still have, that we treasure.

You’re reminding us to savor the present but also to heed the warning signs and take action.

I wanted to go down two roads at once—to speculate how the future might look back at us with longing. Yes, there’s a vast extinction of species going on, rising temperatures, rising seas, and so on. But on the other hand, if you stop doing bad things to the Earth, it pushes back with amazing speed. We have possible catastrophes looming, and we also still have the power to avoid them.

As much of a threat as climate change poses, the novel posits that equally dangerous is a resulting “metaphysical gloom.”

By that I mean that there’s a certain attitude that comes with speculating about the future and climate change, which in the novel I term “metaphysical gloom.” You hear ordinary people saying, “I don’t think my grandchildren are going to have as good a life as I did.”