Hoop dreams

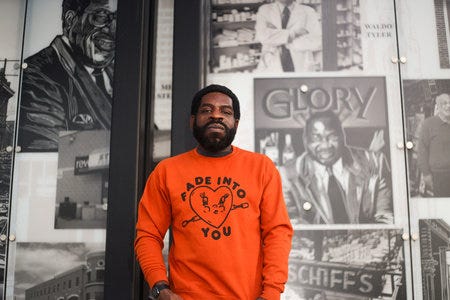

Author Hanif Abdurraqib on how Americans find meaning in sports, the poetry of place, LeBron James, and what it means to make it

What does it mean to make it?

Basketball legend LeBron James knows something about the answer to that question, and this week he led the U.S. Olympic team into the opening ceremonies in Paris, the first men’s basketball player to lead Team USA.

James, the greatest player of the modern era and arguably one of the greatest of all time, hails from Ohio, as does poet, critic, essayist, and novelist Hanif Abdurraqib, arguably one of the greatest American writers of our moment. Abdurraqib’s latest book, There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, is a memoir and love letter to his home state and city (Columbus, Ohio), and to the sport of basketball, all framed by an investigation of LeBron’s relationship with the state and the feelings of Ohioans for their prodigal superstar.

While the book is structured like the game: introduced with a pre-game show, divided into quarters, with a half-time break and a shot clock counting down the seconds towards its conclusion, it isn’t a basketball book. Abdurraqib’s vision of how Americans find meaning in culture alone and together is expansive enough that this book is equally affecting whether you’ve shot free throws at the park until the sun went down or you’ve never set foot on a basketball court at all.

We talked to Abdurraqib about making it in America, the significance we find in the places we grow up and in the places we run away from or return to, the shared meanings we find in popular culture, basketball, and, of course, LeBron James.

A request for those who haven’t yet joined us: The interviews and essays that we share here take research and editing and much more. We work hard, and we are eager to bring on more writers, more voices. But we need your help to keep this going. Join us today to support the kind of independent media you want to exist.

There’s Always This Year captures how sports makes meaning for people. You tell the story of your life, and of the place where you grew up, in parallel with the stories of the high school players you grew up admiring — or not admiring — and the arc of LeBron James's career, his leaving Ohio and returning as you have.

Could talk a little bit about why you told the story this way, through the cultural touchstone of sports, which is so central to American identity in so many ways?

I grew up loving basketball and playing basketball, but I grew up in a very specific era, in a very specific neighborhood, these kind of neighborhoods that often only get ascribed to New York or the coast. But I grew up in a neighborhood at a real time in the '90s on the east side of Columbus. And I grew up across the street from a park, a capital P park. The park on the east side where everyone came to play. Which meant that high school stars from across the city would come and play there.

But the park is a democratized space in a way where if you're the guy who got cut from his varsity team that year and you're on a hot streak and you hit three three-pointers in a row, then that's your day. You are the All-American.

And I was interested in this. I was interested in how I, a marginal player who's 5'7", could have these days on that court against all-state basketball players and how that brought me closer to them, even if for a moment. Even if we didn't share the same social capital within the hierarchy of neighborhood and school or whatever. Or even if my legacy or legend was never going to grow to match theirs, I would have a day where I can say, "We played a game of 5 on 5 to 12, and I scored 8 of that 12, and no one could touch me."

I was interested in that, but I was also interested in this idea of “making it,” this question of what it is to make it, how many ways can you make it? Because the great story of making it, of course — out of Ohio, at least — is the story of LeBron James.

But to me, making it also means the guy who was a high school legend, a street ball legend, who dropped out of school, but every time you mentioned that person's name on the block they grew up on, people revere it.

I write about Esteban Weaver in the book. There are kids on courts right now who weren't even alive when Esteban Weaver played, who know his name. To me, that's making it. That has to be accounted for. That's a kind of making it. A lot of my thoughts around this were about deconstructing hierarchies around success, around making it, around greatness, and the emotional connections built in that process.

You're talking about a cultural idea of making it. The path you've chosen, being a writer and commentator, and public intellectual, that's one way of making it.

There are other ways. The reason people might know who Esteban Weaver is nowadays is because of the internet and because of this democratization of the way people make meaning out of cultural signifiers and personalities. That stuff was one eally local. Nobody knew about the high school might-have-beens outside of the circle of serious players in a given town. But now everybody knows about all of them.

How has the way we do culture now changed that idea of making it that you're dealing with?