Fables of the Reconstruction

Author Zaakir Tameez on what the 19th-century struggle to abolish slavery teaches us about the future of the fight for civil rights.

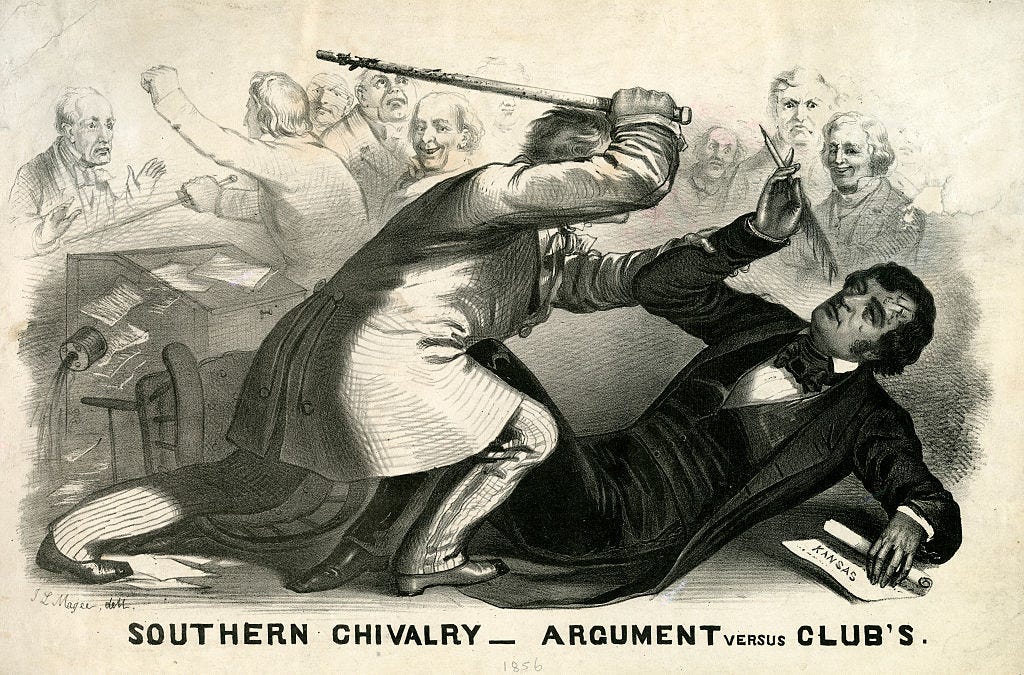

You may remember that U.S. Senator Charles Sumner was beaten on the Senate floor on May 22, 1856, but — off the top of your head — do you recall why? But more on that in a minute.

Last week, in a stunning act of violence against an elected official, California Senator Alex Padilla was silenced, thrown to the ground, and handcuffed after objecting to a speech delivered by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem. Most reports focused on what happened to Padilla, rather than on Noem’s shockingly antidemocratic speech, which motivated him to challenge her in the first place.

It’s understandable — a breach of norms is easier to grasp than the political threat. But following the murder early Saturday of Minnesota State Rep. Melissa Hortman and her husband (and the wounding of State Senator John Hoffman and his wife by the same assassin), it’s imperative not to simply explain things away as violations of norms, or even as “political violence” — and to understand the deeper threats to freedoms that drive these acts.

That takes us back to the caning of Charles Sumner, and how that event’s place in the national memory reveals just how red a line the country has crossed this week. When South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks beat Sumner nearly to death following a speech in the Senate chambers, he did it because Sumner had accused pro-slavery agitators in the Kansas Territory of being a threat to American democracy. As competing accounts emerged, Brooks became as much of a hero in the South as Sumner became in the North, and the beating itself was seen as a precipitating event of (or even an opening salvo in) the Civil War — not necessarily because it exposed the depth of political division over slavery, but because it marked the "breakdown of reasoned discourse" around it.

In his first book, Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation, legal scholar Zaakir Tameez looks beyond that event and how we remember it, reexamines Sumner’s life and career, and depicts him as a philosophical and legislative pioneer of civil rights and an essential moral voice for his time and ours.

Below, we present an excerpt from the book, along with our conversation with Tameez about how and why it makes sense to reexamine Sumner now, just how advanced his views on universal rights were during a period when compromise seemed necessary to preserve the Union, and how he was a canny political strategist with lessons for those looking to turn moral authority into practical victories and s renewed patriotism even today, as the progress towards multiracial democracy built on the Reconstruction Amendments comes under increasing threat.

What do we learn from taking a fresh look at Charles Sumner today, with a government in power that’s looking to undo all the things that Sumner and the Republicans of his era tried to accomplish after the Civil War?

The major biographies frame Sumner as an agitator who exacerbated “sectional tensions” that helped to lead to the Civil War, which was presented as a national tragedy that should have been avoided.

I look at that story and I think, "Gosh, the Civil War was a tragedy in many respects. I mean, more than 700,000 Americans died. But the Civil War also liberated more people than the American Revolution, liberating four million enslaved people. The Civil War in Sumner's eyes was a victory. It was the greatest act of emancipation, perhaps, in world history. And when you look at it from that frame, I think a lot of Sumner's life becomes more compelling and more resonant today.

There’s the story of the caning of Charles Sumner, when, after Sumner gives a speech, a Southern congressman comes up with a cane and nearly beats him to death. That’s often presented as a story of partisanship gone awry; he gave a provocative speech, breaching decorum.

And the beating is also presented as a breach of decorum.

Norm broken on both sides. Surprisingly little attention has been given to the speech that Sumner gave prior to the caning, titled “The Crime Against Kansas.” And that speech is calling out Democrats and referring to the crisis in Kansas where Sumner's former colleague, a man named David Rice Atchison, the former president pro tempore of the U.S. Senate, goes back to Missouri where he's from, organizes a gang of hundreds of armed men, and goes into Kansas, takes over locations at gunpoint, and starts organizing a pro-slavery insurrection.

Sumner was drawing attention to one of the most antidemocratic actions in the history of the United States by a former politician. It’s perhaps the most important pro-democracy speech of the era. He's putting himself at risk by drawing attention to this crisis. Then he gets beaten and nearly killed for it. He nearly died for democracy.

He was willing to exercise that courage because he believed that he needed to galvanize a public that had been asleep to the democratic crisis. That speech was a way to draw attention to it. And the caning was used by the Republican Party and by Summer himself as a way to build momentum for the pro-democracy movement.

Your focus is on the later period of Sumner’s life, on Reconstruction and the attacks against it. What arguments, left unsettled then, have gotten us to this point today?