Borders are violent things

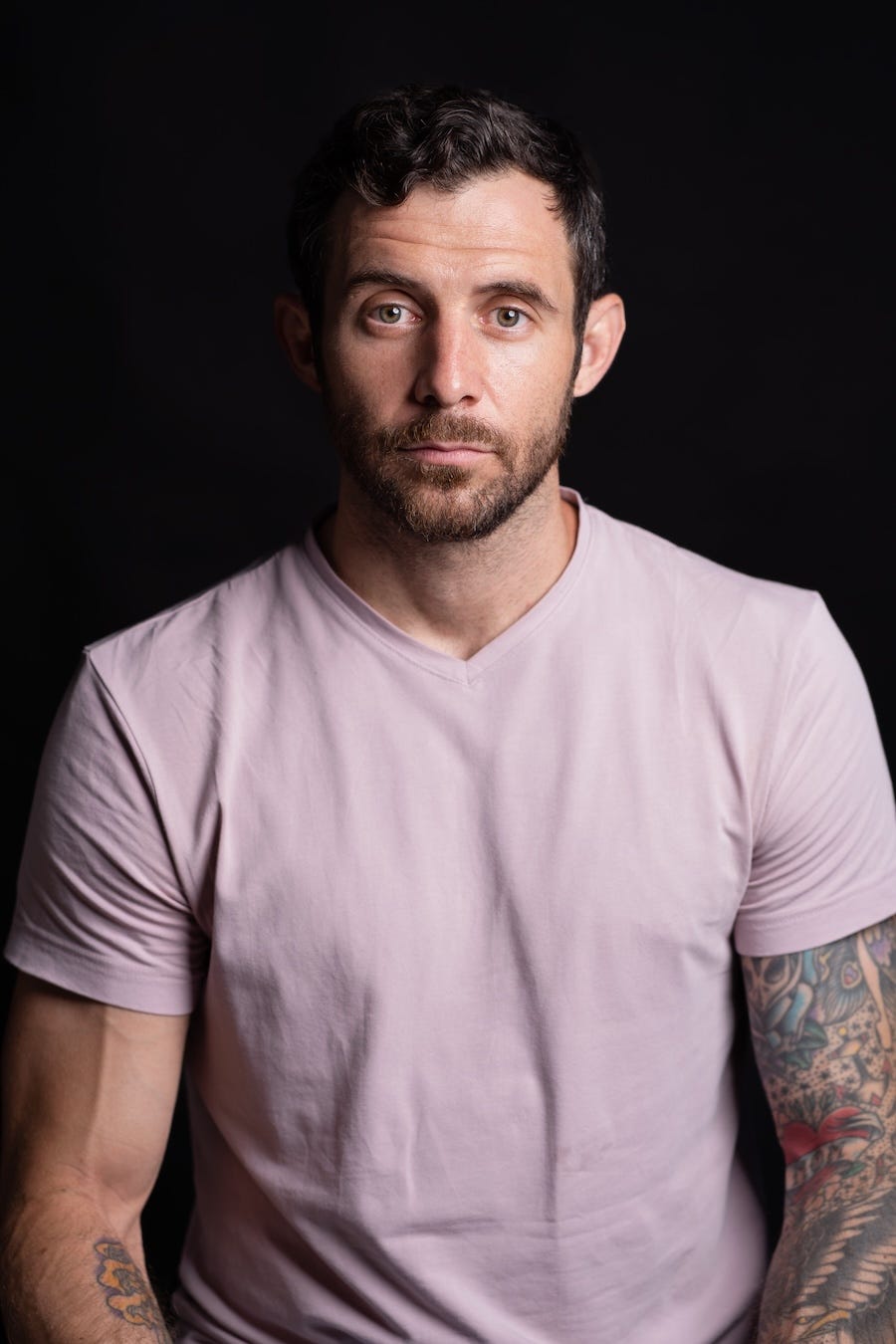

Journalist Patrick Strickland on the far right's attack on asylum, and what Americans can learn from the long struggle against fascism in Greece

How has the far right been able to turn the resentment of refugees into political power so consistently?

In his new book, You Can Kill Each Other After I Leave: Refugees, Fascism, and Bloodshed in Greece, journalist and author Patrick Strickland looks to answer that question, and finds in Greece’s experience over the five decades since the fall of the far-right military dictatorship in 1974 a model for understanding the international turn to the right — and for how to fight back.

Even after the end of the junta, the right never entirely disappeared from democratic Greece, and during the economic crisis of the late 2000s, Golden Dawn capitalized on anti-immigrant and anti-EU sentiment to transform itself from a neo-Nazi street gang to a serious political force. In the process, it mainstreamed far-right ideas and inspired ascendant right-wing nationalist movements and political parties across Europe and in the United States. But when a Golden Dawn member murdered anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas in 2013, it made international news, turned public sentiment against the far right, and ultimately led to a criminal investigation and trial that pushed the party out of Greek politics.

But the damage had been done. In 2015, the year of the refugee crisis, hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers from the Middle East and North Africa began to make the dangerous Mediterranean crossing for camps on Greece’s Aegean islands, fueling resentment of the new arrivals. By then, even as left parties led the government, Golden Dawn’s anti-immigrant positions had become mainstream, and Greece’s border policies helped push other European countries further to the right.

We talked to Strickland — who has lived in and reported from Greece for a decade — about the country’s struggle with resurgent fascism since the economic crisis and in the context of a Europe-wide shift towards closed borders, the connections between right-wing movements in Europe and the U.S., how fascists have built up resentment against refugees and asylum seekers as a tool for power in Greece and around the world, how ordinary people have been able to fight far-right forces in Greece — and how Americans might follow their example to push back against the Trump regime.

Your new book is about the Greek experience of fascism — how authoritarian, nationalist ideas are built and gain popular support in the first place, and then the experience of emerging from them. But you tell the story through the lens of migration, of desperate people fleeing violence in the Middle East, in Eastern Europe, in North Africa, violence created largely by Western and European intervention in those places. And they seek safety, some of them in Greece, where they face this tidal wave of resentment that reanimates the fascists, who’d been out of favor since the fall of the military government in 1974. Why and how did human migration become such a flashpoint?

Well, a little bit of backstory on how I came to this is that I spent the first four-and-a-half, five years of my journalism career in the West Bank and Gaza. And so I had been living there, covering pretty much anything you could cover at the time: the situation, for Palestinians losing their land to settlements, Palestinians in Gaza. I was there for the 2012 and the 2014 wars and the aftermath of those in Gaza. And I'm seeing that massive level of destruction.

And so the idea that people have no choice but to seek safety was just such an obvious thing. And the idea of culpability of what people call the West at large, and the United States in particular, was just — It's impossible to live there and report on that, and not have that idea ingrained.

2015 was the first time I heard from somebody personally who had a connection to people who had tried to take a boat across the Mediterranean. I was in Lebanon in a refugee camp and this Palestinian woman in her seventies there, who had been displaced from Syria — she was born in what became Israel, and grew up in Yarmouk refugee camp, and then had been displaced to a Palestinian camp in Lebanon — she had lost 7 or 8 of her relatives when they tried to take a boat. They had gone from Lebanon to Libya and then tried to go to Italy. That would have been March 2015.

I saw it in the news then. I knew it was happening. But this was a few months before the death of Alan Kurdi in the summer of 2015, which just busted everything wide open.

The refugee crisis year.

What's called the refugee crisis, right? And some people take issue with that term. I think because, in a very well-intentioned sense, they view it as a kind of deflection. They think this is a crisis of management, not a crisis of numbers.

That becomes very important in the U.S. context.

I think that's true. But it's still a crisis for the people themselves because of the inability to manage it. So in 2015, when I first came to Greece. I had been reporting on Palestinians, Lebanon, and Syria for years, and I was really well acquainted with the reasons people were leaving and how badly they needed protection.

When I first came here, I had a sense of great hope, and I still do even a decade later, because the amount of solidarity that I saw then was really heartwarming. People in the neighborhood where I live now, Exarchia, were taking over abandoned buildings, and then refashioning them into housing for refugees, so they didn't have to live in these very squalid and decrepit camps, and that to me was solidarity in in action, you know, in a tangible way, and the backdrop of the far right at that time is that it had actually gone through its biggest wave of of violence before that, from 2011 to 2013, and it was not doing a very good job in 2015 of capitalizing on any discontent that people had.

In fact, most Greeks that I spoke to would mention they were still in their economic crisis, which was crushing, and they would blame the same EU policies that left them jobless or their wages plummeting for the the tragedy of people drowning in the Mediterranean, and I thought that that was a great sign of hope at the time.

Of course, solidarity sort of withered in the years to come.