BOOK CLUB: Giving thanks

Gratitude is real -- but Thanksgiving's mythical origin story is not

Join us at the next Ink Book Club meeting on Wednesday, November 26, at 12:30 p.m. Eastern when we announce our December pick. Watch on desktop at The Ink or join us from a phone or tablet with the Substack app. The Book Club is open to all supporting subscribers of The Ink, so join us now to take part!

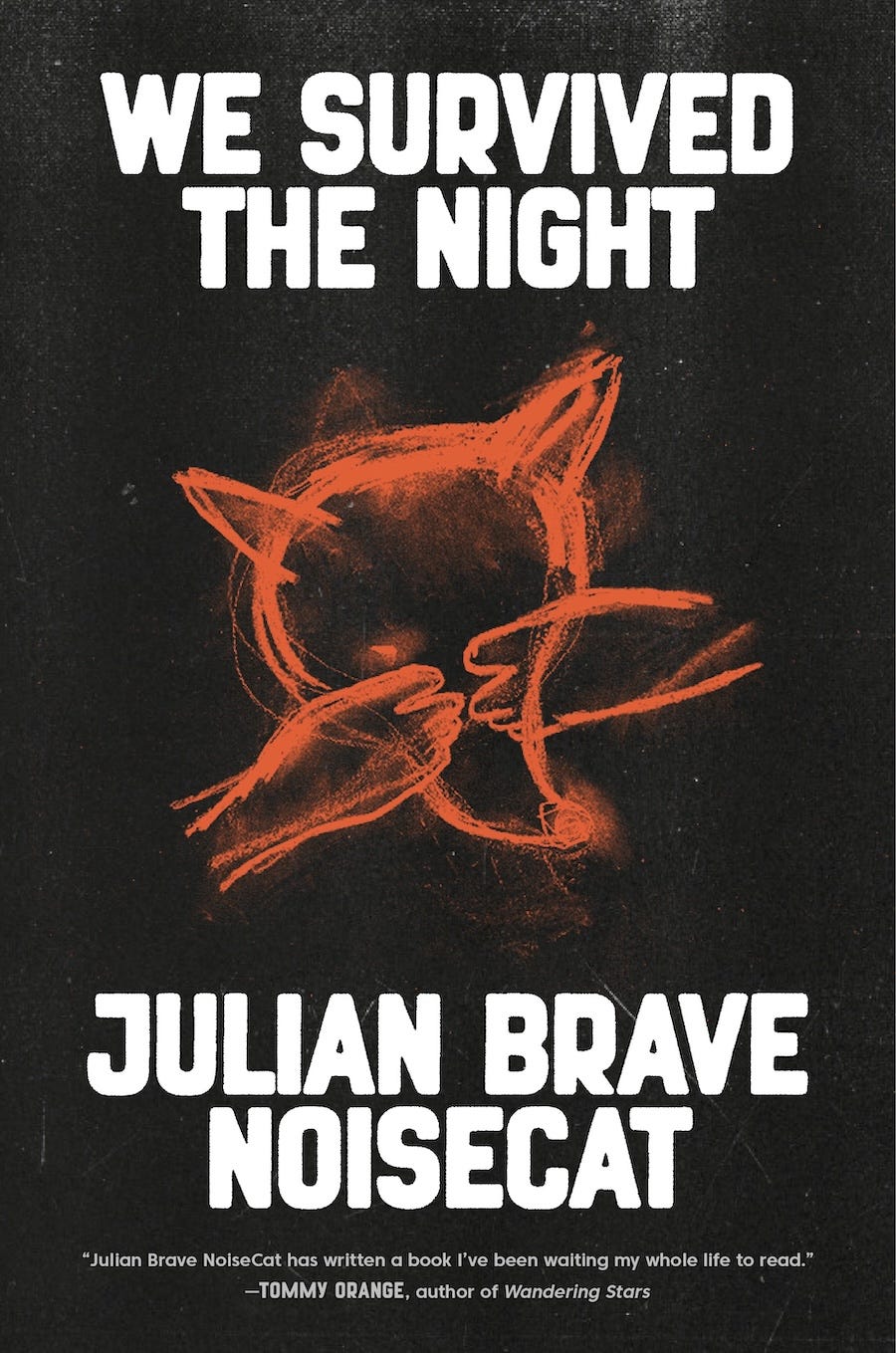

Last Wednesday, the Ink Book Club had a wide-ranging and eye-opening conversation with author Julian Brave NoiseCat about the origins of his book We Survived the Night and the documentary he co-directed, Sugarcane. He described the synchronicity that led him to live a more indigenous life, to reconnect with his father (and even to move in with him), to uncover the long-buried truths that have haunted his family for generations, to retell the oral histories and myths of his Secwépemc ancestors (including the stories of the trickster Coyote, from whom his people claim descent), and to restore centuries of collective wisdom to their rightful place alongside the other important canons of the Western world.

This week, we’ve been thinking about how to understand the Thanksgiving celebration in light of the Native experience. We asked NoiseCat for his perspective:

I think the right way to look at Thanksgiving is as a bunch of Pilgrims being invited to a Wampanoag feast. Feasting is one of the oldest Indigenous and human traditions. My people and all people have some form of feasting in our culture and it is always an act of generosity and friendship. So in that sense I don’t really see it as an American celebration. I see it as an Indigenous way of gathering, sharing, and relating that America thinks is its own. Because America never really understands how much of its American things are actually Indigenous things.

I do usually celebrate with my mom and family and friends on that day. And I have been going around telling strangers “Happy Thanksgiving!” this week in a cheerful tone. When they give a friendly response, I follow up with an equally cheery: “Be nice to the Indians!”

Because when people invite you in for a feast on their land, you’re supposed to reciprocate that generosity. That’s our way. And it’s the least this country could do. But of course it never has.

In the autumn of 1621, on the “First Thanksgiving,” fifty-two English settlers joined some ninety Wampanoag people near what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, to mark a successful harvest.

On landing, the Mayflower settlers had been met by the Wampanoag, some of whom, like Tisquantum, or Squanto (who had been taken captive by an earlier expedition and had lived in Europe), already spoke English. While tribal leaders were wary of these latest would-be colonizers, the Wampanoag people had been decimated by illness (likely carried by previous European visitors), and for strategic purposes (including protection from the neighboring Narragansett), they forged an alliance in March of 1621. The Wampanoag also shared their knowledge of hunting and planting, and likely saved the Pilgrims from starvation.

For three days that fall, the new allies gathered together in gratitude for a successful harvest. They played ball games, danced, sang, and dined on deer, corn, shellfish, and roasted meat. Sadly, though, within a generation of that first Thanksgiving, war erupted, and the Wampanoag, who had inhabited that land for 12,000 years, lost much of it, as well as their political independence.

In subsequent years, those who continued to commemorate that first Thanksgiving observed it as a day of fasting and reflection. In the mid-19th century, Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the magazine Godey’s Lady Book, led a campaign for a national holiday to be built around Thanksgiving, largely erasing the role of the Wampanoag from the story. She lobbied President Lincoln to designate the holiday, and in an effort to inspire unity during the turmoil of the Civil War, it was so decreed in 1863. That holiday was built on a myth—a semi-fictional version of what transpired centuries before.

It’s useful to remember, when we settle in around our tables with friends and family to feast on turkey and pumpkin pie, that for many Native peoples, Thanksgiving isn’t celebratory; it’s also a reminder of the catastrophic impact of European colonization of America’s Indigenous peoples. Which is what makes learning from We Survived the Night and other sources so vital.

And below, for our Book Club members, some questions to get you thinking.

The Ink Book Club is open to all paid subscribers to The Ink. If you haven’t yet become part of our community, join today. And if you’re already a member, consider giving a gift or group subscription.