BOOK CLUB: George Saunders points us in the direction of kindness

A Book Club member's read of "Vigil" highlights a moral quandary, plus some words of advice from the author

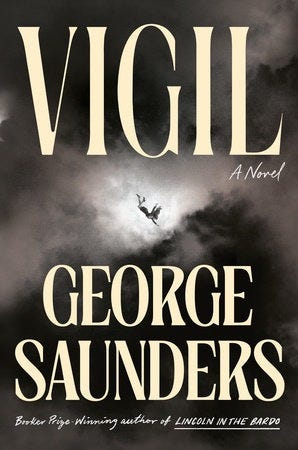

In the face of news that grows ever more difficult to comprehend or accept, George Saunders’s Buddhism-infused kindness offers an alternative to free-falling outrage, and Vigil — Saunders’s second novel and our February Ink Book Club pick — is a sort of literary Rorschach test, with each reader deriving something different from it.

In this past week’s discussion of the novel, one of our Book Club members, Terrence Green, offered an incisive assessment of how kindness functions, and gets at one of the book’s central puzzles: what does an angel of forgiveness do when called upon to comfort someone who — it would appear — neither deserves forgiveness nor desires it? Boone is, as Jill observes, “as sure of himself as ever a charge of mine had been.”

Is there even a path towards “closure” here, as we’d typically understand it?

“Some things have to be accepted,” Terrence wrote, “if we’re going to stay honest about reality, and other things remain open to change… Vigil is about learning how to live inside that distinction.”

Terrence’s reading — in a way, a recasting, he suggests, of the Serenity Prayer — put us in mind of a passage from Saunders’s now-famous 2013 Syracuse University commencement address, in which he urged students to “err in the direction of kindness.”

As Saunders addressed the students at Syracuse in 2013:

“Becoming kinder” happens naturally, with age. It might be a simple matter of attrition: as we get older, we come to see how useless it is to be selfish — how illogical, really. We come to love other people and are thereby counter-instructed in our own centrality. We get our butts kicked by real life, and people come to our defense, and help us, and we learn that we’re not separate, and don’t want to be. We see people near and dear to us dropping away, and are gradually convinced that maybe we too will drop away (someday, a long time from now). Most people, as they age, become less selfish and more loving. I think this is true. The great Syracuse poet, Hayden Carruth, said, in a poem written near the end of his life, that he was “mostly Love, now.”

The Ink Book Club is open to all paid subscribers to The Ink. If you haven’t yet become part of our community, join today. And if you’re already a member, consider giving a gift or group subscription.